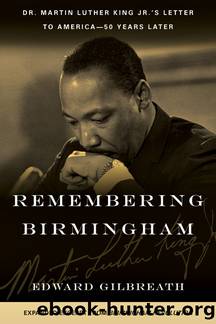

Remembering Birmingham by Edward Gilbreath

Author:Edward Gilbreath [Gilbreath, Edward]

Language: eng

Format: epub

Tags: Religion, Christian Living, General, Social Science, Discrimination

ISBN: 9780830866632

Google: gOv0qi14IjwC

Publisher: InterVarsity Press

Published: 2013-03-04T05:21:33+00:00

3

âMy Dear Fellow Clergymenâ

Dated April 16, 1963, Kingâs letter was ostensibly addressed to the eight white clergymen who had deemed him an âoutsiderâ and called his movementâs presence in Birmingham âunwiseâ and âuntimely.â King explains that, as a rule, he avoids responding directly to the multitude of criticisms leveled against him. But because he senses these brothers are âmen of genuine goodwillâ and that their âcriticisms are sincerely set forth,â he endeavors to answer them in âpatient and reasonable terms.â

He begins, âMy Dear Fellow Clergymen,â but it becomes evident fairly quickly that he isnât just aiming his missive at Harmon, Hardin, Carpenter, Durick, Grafman, Murray, Ramage and Stallings. No, for him the Birmingham Eight were essentially surrogates for the larger watching world. King is also going after Birminghamâs new Mayor Albert Boutwell, Commissioner Bull Connor, Birmingham World editor Emory Jackson, businessman A. G. Gaston, President John F. Kennedy, Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy, Billy Graham, National Baptist Convention president J. H. Jackson, and every other American, white or black, who felt Negroes should slow their proverbial roll or who doubted the Judeo-Christian foundation of civil disobedience and nonviolent resistance.

âLetter from Birmingham Jailâ marks a synthesis of concepts and philosophies King had been working out for years in speeches, articles and even in his seminary and postgraduate work. It represents, in the opinion of one historian, âa culmination of all of Kingâs ideas, theology, experiences, and civil rights tactics.â His approach is at once redemptive and subversive. There is, in effect, a method to his meekness. Notes Thoreau scholar Wesley T. Mott: âKingâs conciliatory toneâwhile apparently conceding ground in its humilityâis intended to reveal the inhumanity of the clergymenâs position and to hold it up to the scorn of those of us who are reading over their shoulders.â

King works hard to establish a tone of cordial discourse, but through each sentence, one can feel his fierce indignation teeming below the surface. When the letter finally found its way to the Birmingham Eight, they no doubt felt it too.

He likens himself to the apostle Paul, who traveled throughout Greece and Asia Minor preaching and launching churches (and who also, coincidentally, spent a lot of time writing letters to the church from behind bars). King cites the âMacedonian callâ in which a man appears to Paul in a dream, asking him to âcome over to Macedonia and help usâ (Acts 16:9). Like King, Paul was persecuted, arrested and ultimately executed for preaching an unpopular message. King connects his own situation to Paulâs sufferings and thus ascribes a level of biblical legitimacy to his ministry of social justice. He justifies his presence in Birmingham by appealing to âthe interrelatedness of all communities and statesâ and declaring that his quest for human rights transcends jurisdiction. He could not âsit idly by in Atlantaâ while hell was breaking loose in Birmingham. Injustice anywhere threatens justice everywhere, he said.

To the criticism that the Birmingham demonstrations were ill-timed, King counters that those in privileged positions cannot be depended on to yield their power voluntarilyâthey must be compelled to do the right thing.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

Cecilia; Or, Memoirs of an Heiress — Volume 1 by Fanny Burney(32527)

Cecilia; Or, Memoirs of an Heiress — Volume 2 by Fanny Burney(31928)

Cecilia; Or, Memoirs of an Heiress — Volume 3 by Fanny Burney(31916)

The Great Music City by Andrea Baker(31899)

We're Going to Need More Wine by Gabrielle Union(19020)

All the Missing Girls by Megan Miranda(15889)

Pimp by Iceberg Slim(14464)

Bombshells: Glamour Girls of a Lifetime by Sullivan Steve(14038)

For the Love of Europe by Rick Steves(13817)

Talking to Strangers by Malcolm Gladwell(13331)

Norse Mythology by Gaiman Neil(13317)

Fifty Shades Freed by E L James(13216)

Mindhunter: Inside the FBI's Elite Serial Crime Unit by John E. Douglas & Mark Olshaker(9295)

Crazy Rich Asians by Kevin Kwan(9261)

The Lost Art of Listening by Michael P. Nichols(7476)

Enlightenment Now: The Case for Reason, Science, Humanism, and Progress by Steven Pinker(7287)

The Four Agreements by Don Miguel Ruiz(6728)

Bad Blood by John Carreyrou(6600)

Weapons of Math Destruction by Cathy O'Neil(6248)